The Battle of Stirling (1297)

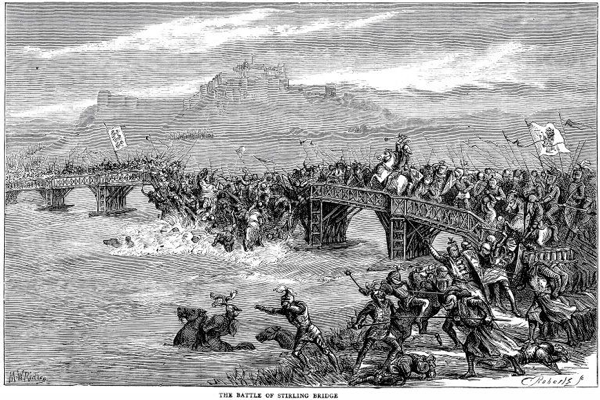

The Battle of Stirling Bridge was the first major Scottish victory in the Wars of Independence, placing the country back under Scottish control and raising William Wallace to a position of political dominance.

First War of Scottish Independence

The Battle of Stirling occurred during the First War of Scottish Independence. Although nobody was to realise it at the time, the retrospectively named First War of Scottish Independence was only the first in a series of wars between the Scottish and the English. The wars were all caused by English kings attempting to establish authority over Scotland, whilst the Scots fought to keep the English rule and authority out of Scotland.

The war began with the English invasion of Scotland in 1296, and lasted until the restoration of Scottish independence with the Treaty of Edinburgh-Northampton in 1328. It can be loosely divided into four phases:

- The initial English invasion and success in 1296

- The campaigns led by William Wallace, Andrew Moray and other Scottish Guardians from 1297 until 1304 (inclusive of the Battle of Stirling)

- The renewed campaigns led by Robert the Bruce between his coronation in 1306 and the Scottish victory at Bannockburn in 1314

- And a final phase of Scottish diplomatic initiatives and military campaigns in Scotland, Ireland and Northern England from 1314 until the Treaty of Edinburgh-Northampton in 1328.

The Battle of Stirling Bridge in 1297 was one of the many battles that made up this war.

The Background of the Battle of Stirling

The death of the seven-year-old Scottish queen, Margaret, in 1290 left the throne of Scotland vacant. The Scottish lords gave Edward I the task of choosing a new king. He picked the weak John Balliol, a distant descendant of the great Scottish king David I, in the expectation that he would do Edward’s bidding. The English king, however, was quickly disabused of this idea when Balliol refused to join him on campaign in France and, in 1295, signed an alliance with France, England’s traditional enemy.

There was a rebellion, leading to an English campaign involving the sack of Berwick and the defeat of a Scottish army at Dunbar. John Balliol then sued for peace and accepted an English occupation but, in 1297 under the leadership of Sir William Wallace and Sir Andrew Moray, there was a major Scottish revolt.

This was at a time when the English were engaged in war with France and, as so often, the Scottish forces chose this time to challenge their enemy, when they were more vulnerable because fighting on two fronts. By August 1297, Morray and Wallace controlled almost all of Scotland north of the Forth, except for Dundee. As Edward I was fighting on the continent, the English governor, the Earl of Surrey, marched north with an army from Berwick to relieve Dundee.

It was at the crossing of the Forth at Stirling that the Scottish army chose to meet the challenge in what became known as the Battle of Stirling.

William Wallace

Little is known of William Wallace before the events of 1297, other than he was born near Paisley. He was first mentioned by English contemporary sources as an outlaw, who is reported to have killed the English Sheriff of Lanark, in May 1297.

He then led a rebellion across Scotland, attacking English soldiers and officials, and was supported by important figures such as Bishop Wishart of Glasgow, the noble Sir William Douglas and Robert the Bruce. However, although many nobles supported him openly at first, they surrendered to Edward’s nobles at Irvine in July 1297.

Wallace himself refused to surrender and continued his fight against English occupation. He probably avoided capture in the summer months by hiding in Selkirk Forest, before moving north at the end of the summer and meeting with Andrew Moray near Dundee ahead of the Battle of Stirling.

Andrew Moray

The Scottish patriot Andrew Moray, freedom fighter and military strategist, is often not as well documented in the history books as his partner in attempting to expel the English from Scotland, William Wallace.

In 1296, Andrew Moray and his father were captured by Edward at the Battle of Dunbar. His father was sent to the Tower of London and died in captivity. Andrew was imprisoned in Chester Castle but escaped the following year and headed north. He crossed the border and raised his father’s standard in May 1297 at Avoch Castle on the Black Isle – heralding a rebellion.

In September 1297 Andrew Moray and Wallace joined forces and the Scots prepared for Battle of Stirling. It is widely though that Moray made the battle plan – picking the ground and deciding the tactics.

The Main Battle of Stirling

In the heart of Scotland, Stirling and its Castle had crucial strategic importance. Whoever controlled Stirling could then control movement between the north and south of the Kingdom.

The English Army

The English army was led by the Earl of Surrey, who was Edward I’s lieutenant in Scotland, and Hugh de Cressingham, the Treasurer of Scotland. Neither of these men saw either Wallace or Moray as a threat and they expected to crush the rebel Scots.

De Cressingham was hugely unpopular amongst the Scots and his presence undoubtedly antagonised the men of Wallace and Moray. The Earl of Surrey’s attitude at Stirling may have contributed to the English defeat too.

Before the fighting began, he had already sent some of his soldiers home, to save paying their wages, and he believed that the English army would easily defeat Wallace and Moray. Not only that, but he slept late on the morning of the Battle of Stirling and could not decide how to get his army across the river and took too much time to do this.

The Arrival of the Scots

The Scots arrived and camped on Abbey Craig, which dominated the soft flat ground north of the river. The English force of English, Welsh and Scots knights, bowmen and foot soldiers were camping south of the river.

Sir Richard Lundie, a Scots knight who joined the English after the Capitulation of Irvine, offered to outflank the enemy by leading a cavalry force over a ford two miles upstream, where sixty horsemen could cross at the same time. Hugh de Cressingham, King Edward’s treasurer in Scotland, persuaded the Earl to reject that advice and order a direct attack across the bridge.

The small bridge was broad enough to let only two horsemen cross abreast but offered the safest river crossing, as the Forth widened to the east and the marshland of Flanders Moss lay to the west. The Scots waited as the English knights and infantry began to make their slow progress across the bridge on the morning of 11 September. It would have taken several hours for the entire English army to cross.

Wallace and Moray waited, according to the Chronicle of Hemingburgh, until “as many of the enemy had come over as they believed they could overcome”. When a substantial number of the troops had crossed (possibly about 2,000) the attack was ordered.

The Scots spearmen came down from the high ground in rapid advance and fended off a charge by the English heavy cavalry and then counterattacked the English infantry. They gained control of the east side of the bridge and cut off the chance of English reinforcements to cross. Caught on the low ground in the loop of the river with no chance of relief or of retreat, most of the outnumbered English on the east side were probably killed. A few hundred may have escaped by swimming across the river.

Hugh de Cressingham himself was killed and was supposedly skinned and cut to pieces by the Scots.

The Earl of Surrey, who was left with a small contingent of archers, had stayed south of the river and was still in a strong position. The bulk of his army remained intact and he could have held the line of the Forth, denying the Scots a passage to the south, but his confidence was gone.

So Surrey ordered the bridge to be destroyed and retreated towards Berwick, leaving the garrison at Stirling Castle isolated and abandoning the Lowlands to the rebels. James Stewart, the High Steward of Scotland, and Malcolm, Earl of Lennox, whose forces had been part of Surrey’s army, observing the carnage to the north of the bridge, withdrew. Then, the English supply train was attacked at The Pows, a wooded marshy area, by James Stewart and the other Scots lords, killing many of the fleeing soldiers.

The Aftermath

The Battle of Stirling Bridge was a shattering defeat for the English which showed that under certain circumstances, infantry could in fact be superior to cavalry. The English losses in the battle have been recorded as around 100 cavalry and 5,000 infantry killed. Scottish casualties in the battle are unrecorded, with the exception of Andrew Moray, who appears to have been injured in the battle and died of his injuries around November.

Wallace went on to lead a destructive raid into northern England, which did little to advance the Scots’ objectives any further, but did at least frighten the English army and stalled their advance. By March 1298, he had emerged as Guardian of Scotland.

The Battle of Stirling Bridge is depicted in the 1995 film Braveheart, but it bears little resemblance to the real battle, there being no bridge (due mainly to the difficulty of filming around the bridge itself).

Present-day Stirling Bridge

The Stirling Bridge which was key to this Battle’s success is believed to have been about 180 yards upstream from the 15th-century stone bridge that now crosses the river. Four stone piers have been found underwater just north and at an angle to the extant 15th-century bridge, along with man-made stonework on one bank in line with the piers.

The site of the fighting was along either side of an earthen causeway leading from the Abbey Craig, atop which the Wallace Monument is now, to the north end of the bridge. The battlefield has been inventoried and protected by Historic Scotland under the Scottish Historical Environment Policy of 2009.

What you should do next...

- Browse our plots to claim your title of Lord or Lady of the Glen

- Discover the masjetic Kilnaish Estate

- View our fun gifts and accessories, inspired by the Scottish Highlands