A Guide To Midges in Scotland

The Scottish Midges often loom like a cloud over the idea of a pleasant camping holiday or walk in the countryside.

They have ruined many a time in the great outdoors and some have been known to reduce grown men and women to tears. They also cause problems for outdoors industries in Scotland, reducing productivity and menacing those who make their living working outside.

Without the midge, Scotland would not be the same. Midges are one of the reasons for the relatively low population of the Scottish Highlands and help keep the wildernesses wild. They help to keep large areas free of human interference than they may otherwise have been. What is more, they are a food source for a number of important wild creatures, such as bats.

In order to understand these oft-dreaded little creatures a little better, let’s take a look at them in a little more depth.

01. What Are Midges?

Midges in Scotland are a type of tiny insect of the order Diptera and the suborder Nematocera. Midges are found in practically every environment on earth, except the permanent cold deserts of the poles and the permanent hot deserts of arid zones.

The Scottish midge (also referred to in Scotland as midgies (mi-jees) or ‘wee beasties’) belongs to a family of midges known as Ceratopogonidae – biting midges. Other members of this family are known as ‘no see ums’ in North America, and have been implicated as vectors for the spread of disease-causing pathogens in the tropics and elsewhere in the world.

What is the difference between Scottish midges and mosquitoes?

If you’re unfamiliar with Scottish dialect, you might easily mistake midges for mosquitoes. Both insects bite and draw blood, but only female midges are biters. Scottish midges are tiny, gnat-like flies, about 1-3mm in size, and often grey unless they’ve recently fed, in which case they turn red.

Midges thrive in the damp, marshy areas of the Highlands and western Scotland, swarming aggressively during the summer months, particularly in the early morning and late evening. In contrast, mosquitoes are much larger and found globally in warmer climates, making a distinctive loud buzzing noise.

While both insects feed on blood, mosquitoes use their specialised mouthparts to pierce the skin, whereas midges cut the skin with their mandibles before feeding. Unlike midges, mosquitoes are known vectors for serious diseases such as malaria, dengue fever, and Zika virus. Despite both causing discomfort through their bites, midges do not transmit diseases to humans.

02. How Long Do Midges Live?

Midges mate and lay eggs during the summer months each year. The eggs are laid in boggy ground or ground vegetation and hatch into larvae. Egg hatch takes less than 24 hours.

This stage of the life cycle is followed by four larval stages. During larval stages, these creatures live as omnivores/ detritivores in the water films of the surface layers of the soil. The final larval stage then overwinters.

In late spring or early summer, (as day length and temperature increase) there is then a short pupal stage which takes 1-2 days. After this stage, the adult midge will emerge.

Non-biting males will sometimes emerge before the biting females. Sometimes, bivoltinism (a second generation within the midge season), and sometimes even a third generation, takes place. In this case, the generation period is recognised as around 6 weeks.

During the summer mating season, males will find a female with whom to mate and will then die off. The females will lay their first lot of eggs without needing a blood meal. They can then lay up to three further batches of eggs, depending on the weather and their survival, over the summer months, requiring a blood meal for each subsequent batch, before dying off as autumn weather arrives.

03. Midge Bites

As mentioned above, female culcoides impunctatus need an abdomen full of blood in order to lay their eggs and perpetuate the species. It is the fact that they bite humans that has given these midges their fearsome reputation.

The female midge’s mouth parts – fine toothed mandibles and maxillae, work like two saws, cutting through the skin. The midge then excretes saliva into the wound, which keeps the blood from coagulating, creating a pool of blood upon which to feed.

It is the physical way in which a midge bites that accounts for the notorious pain we experience when bitten by them. If left undisturbed, a female midge will remain there, feeding, for 3-4 minutes, taking an average of 2 µl of blood.

When we (or another mammal) are bitten by a midge, the body responds by releasing histamine at the site of the wound. This results in the characteristic itching and swelling of the bite. Some people will have a stronger immune response and will get big red lumps at the site of bites, while other people will see only a small red mark at the bite site.

Why Do Some People Get More Midge Bites than Others?

Those who have spent much time in the Scottish Highlands will already know that some people are more ‘attractive’ to midges than others. Some people can spend time around midges and get few bites, or none at all, while other people can be covered the second they step outside.

Lots of theories, from diet to body type, to being a smoker or non-smoker, have been put forward to explain this phenomenon. In recent years, however, scientists have examined those who midges seem to avoid to see what they have that the rest of us do not.

It seems that it is a specific chemical hidden in body odour that midges seem to hate. This chemical has been identified as ketone. Some people have lots of this natural midge repellent, while others do not. This is believed to be hereditary, and scientists are working on isolating the gene. One day, this may lead to a pill which can turn everyone into a natural midge repelled.

04. Midge Habitat

Culcoides impunctatus in Scotland are found in highest numbers in the Western Highlands. It is here that the ideal midge habitats are found. However, in smaller numbers, midges can be found across most of the country where areas of damp soil for breeding can be found.

Midges prefer to lay their eggs in damp, boggy ground, and acidic peat soils in particular. This is why they are found in the Western Highlands in such high numbers. Female midges tend to bite in close proximity to their breeding site, though they have been found as far as 1km away.

While midges get human blood when they can, the majority of the blood they feed on comes from cattle, sheep, and deer, so they can often be found in largest number close to locations where such creatures can be found.

Midges are worse in sheltered glens than they are on peaks or exposed locations. Midges are far less common at elevations over 500m. Sheltered locations with high rainfall and high humidity tend to be where you will find the highest concentrations of biting midges.

05. Midge Activity & Seasonality

While biting midges are abroad in Scotland between May and September, with some outliers hitting the skies in April and October, July and August are generally considered to be the time when midges in Scotland are at their worst, in the average year.

When Are Midges Worst in Scotland (The Best Time to Avoid Them!)

Astoundingly, during the height of summer, when midges are at their worst, these tiny creatures can be a true impediment to forestry, agriculture, and for all those spending time working outdoors.

The Forestry Authority has estimated that of the 65 working days each summer, as much as 20% can be lost due to midge attacks preventing workers from doing their jobs. The impact of midges on the tourist industry in financial terms is unknown, but it is clear that during peak season, midges do have an important role to play in driving people away from many of Scotland’s wild and beautiful locations. It is estimated that the Scottish tourist industry loses around £268 million each year because holidaymakers stay away during midge season. (Bad news for some, but good news, perhaps, for those who enjoy spending time in nature undisturbed by tourist hordes.)

The times to avoid (when midges are at their worst) can also depend on the weather conditions in a given year. A warm, damp spring can often see midge numbers rocket. Midges are also worse throughout the spring, summer and early autumn when the weather is humid and still. If summer is warm and wet, midges can still be bad later in the summer and into the early autumn, as subsequent generations arise. A late approach of autumn with warm, wet conditions into September can also prolong the midge season.

Interestingly, a harsh, cold winter has little or no effect on midge numbers the following season. In fact, when Scotland had a particularly cold and severe winter in 2010, scientists found that the following summer was actually a bumper year for midges. Midges in the larval stage remained safe below the ground, but the cold weather killed off more of the midge’s natural predators such as bats and birds, and so midge numbers were higher.

You are far less likely to encounter severe midge problems if visiting Scotland when the weather is cloudless and dry. When the sun’s penetration through cloud drops below 260 W/m2, midges come out to play and when it drops below 130 W/m2, midges can reach problem levels.

Higher winds (midges cannot fly in winds over 7mph) can also help to keep midges at bay. A hot, dry June or early July can reduce the likelihood of subsequent midge generations.

If you are planning a camping holiday, or planning to otherwise spend time outdoors in Scotland’s midgier areas during the summer months, checking the weather forecast for the area you are visiting should help you to determine how bad the midges are likely to be.

What Time of Day are Midges Most Active?

Another thing to bear in mind if you are visiting an area where you expect to encounter midges is that they are at their most active in the early morning, just before dawn, and in the evening, as light levels begin to fall. While midges do bite at any time of the day, you are less likely to be bitten if you avoid spending time outdoors at the beginning and end of the day.

The Midge Forecast

Visitors coming to Scotland during the summer months can also check the midge forecast, which will tell you how severe midges are likely to be on a given day in a particular location.

The Scottish Midge Forecast is created using data collected from biting midge traps and mini-weather stations across the country. The data collected is extended nationally using weather forecast data to give a big picture view of midge levels throughout the season.

On the midge forecast, on a map of Scotland, you will see coloured circles with numbers 1-5. These tell you what level midges are at in each part of the country. A level one means – ‘No flies on me’ – few midges, if any, will be detected. A level two means that a location is ‘mostly midge free’.

A level three, and midges can be bad enough that it is a good idea to take measures to ‘make yourself repellent’ or cover-up, at a level four ‘That’s not mist, that’s midges!’ and at level five – midges are pretty much as bad as they get. If you’ve not experienced it – you don’t want to know!

06. How To Get Rid of Midges

The question of how to get rid of midges is one on which scientists have been working hard. The answer depends in part on whether we are looking at the big picture, at the problem of midges in Scotland as a whole, or at the micro-level – how to get rid of midges (at least temporarily) on a small scale.

The question is a complex one, but one to which everyone who knows anything about outdoors life in Scotland thinks that they have the answer.

Keeping Midges Away

When looking at the big picture, the big question often debated is whether or not steps should be taken to eradicate the Highland biting midge from certain areas (or even from the whole of the country).

The arguments for eradicating (or severely controlling) the Scottish biting midge are many and varied. Academics working on the problem argue that midges are costly for the Scottish economy. As mentioned above, they are problematic for productivity levels in outdoors industry (not to mention extremely unpleasant for the workers involved) and cost the tourism industry a huge amount each year.

What is more, while midges do not carry diseases fatal to humans, the same cannot be said for animals. Midges do carry some major livestock pathogens. For example, midges can carry the blue tongue virus, which kills sheep. While this virus has not yet appeared in the UK, it could happen – especially as global warming continues and midges surviving over winter may increase the potential for them to harbour disease.

However, scientists are mostly of the belief that this is unlikely to become a problem within our lifetimes. What is more, from an ecological standpoint, sheep and red deer (another food source for midges) do a lot more damage, due to a lack of predators and unsustainable land management, than the midges do.

Another argument used in favour of widespread midge control (if not outright eradication) is that, while they do play a role in the food chain – eaten by a range of bats and birds and other creatures – those creatures would, if midges were gone, just eat something else.

Existing prey data on bats and birds suggest that controlling (potentially reducing) midge numbers in Scotland would have minimal impact on predatory species. It is believed that midge control only results in a small shift in prey selection in areas of significant midge reduction. The pipistrelle, for example, the most common bat species in Scotland, is known to feed unselectively on whatever insects are available. The same is believed to be true of warblers and other passerines. The impact of the removal of midge larvae from soil ecosystems is also believed to be relatively small since they constitute only a very small proportion of the total soil fauna.

Setting aside the bigger picture for the moment, many ways to get rid of midges focus on keeping midges away from individuals, rather than removing them from an environment altogether. Methods for avoiding midge bites usually fall into two main areas: coverage (to prevent midges from reaching your skin) and repellents (which reduce midge’s attraction to an individual).

Midge Traps

While total midge eradication is not really currently on the table, major forms of midge control are in use around the country.

Currently, midge traps are the most effective and widely used form of midge control. Midge traps are used in problem midge areas to capture midges and reduce midge numbers considerably. They are used in gardens, campsites and in other locations where midge numbers are problematic for humans living or working in the vicinity.

Midge traps work by mimicking a human or other large mammal. They attract midges with a range of different mechanisms, including the release of CO2, moisture and heat, the mimicry of body skin temperature, the use of a rapid action attractant that mimics sweat, and movement mimicked by, for example, a blinking LED light, a water trap, and light.

Once midges are drawn into a midge trap, they are usually drawn into a vessel by a strong vacuum fan. A sticky glue trap with a contrasting pattern is sometimes also used to trap the insects.

While some may object to the idea of killing so many living creatures, midge traps of this kind have been shown to make life more bearable for many who spend time around midges in the great outdoors, and can significantly reduce midge numbers (and therefore midge bites) over smaller areas.

Attracting bats and birds that eat midges is an ecologically friendly way to keep midge numbers down – but the midges they eat are still only a drop in the ocean.

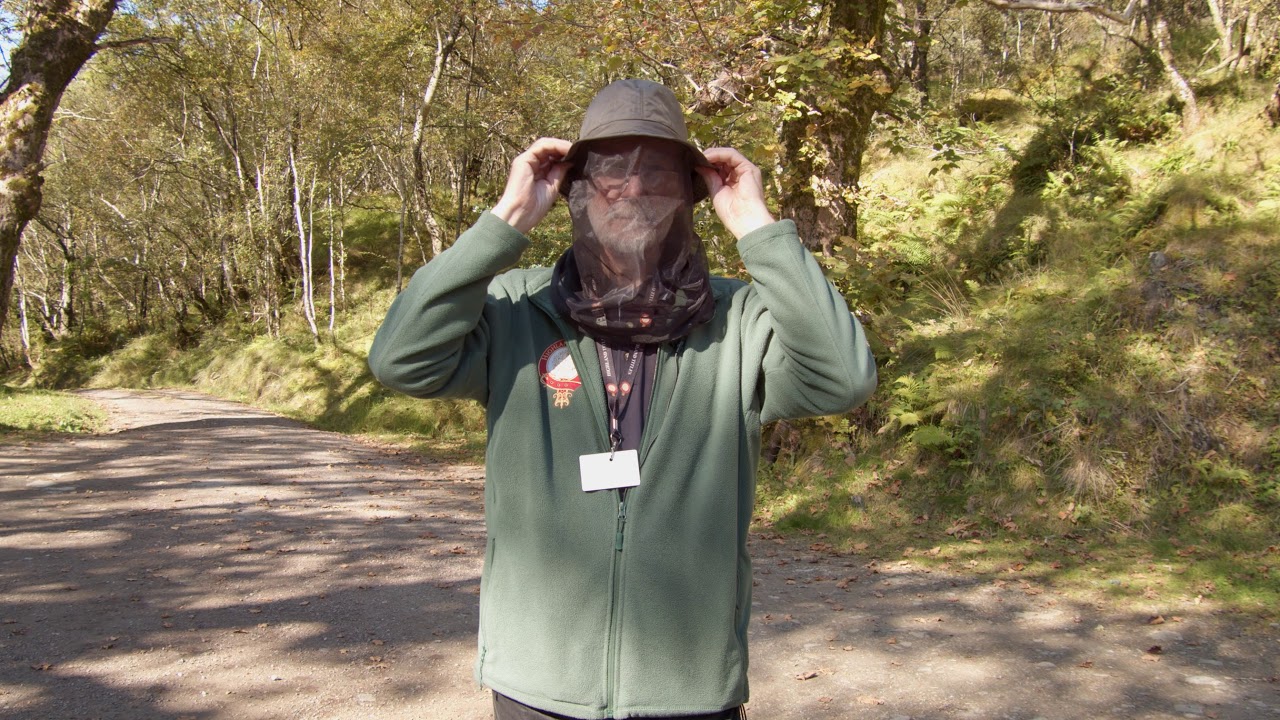

Midge Nets and Coverage

The most effective way of keeping midges off is to employ a technique of total coverage. In a severely midge infested area, clouds of the insects can make it difficult to see, regardless of whether or not you actually get bitten!

You can wear long sleeves and tuck your trousers into your socks, of course, in order to protect your arms and legs. You may also wear gloves to protect your hands. For the face and neck, some visitors to such areas choose to invest in a midge net, which is a mesh hood worn over the head.

This will prevent midges from reaching your skin – as long as you make sure there are no points for them to enter.

Midge Repellents

In addition to covering up, many entering areas where there are midges often also choose to use some form of repellent. There are a number of different repellents that have varying degrees of efficacy when it comes to getting rid of midges and making sure that they do not bite.

DEET Insect Repellents

DEET, a chemical formula of diethyltoluamide, is the active ingredient in many insect repellents. Such repellents do provide a degree of protection against midges and other biting insects. However, though insect repellents containing DEET do not pose a significant danger to human health or the environment, some people can experience negative skin reactions when using such products.

Smidge Insect Repellents

One insect repellent that does not contain DEET and which is found for sale all over the Highlands is Smidge, and many locals will swear by it. The active ingredient in this popular repellent has been designed to effectively block the antennal receptors of biting insects – thereby throwing midges off your scent. It also stops you from tasting so good to the midges.

Natural Insect Repellents

Smearing citronella on any exposed areas of skin will get rid of midges from your immediate vicinity (at least short term), and burning citronella candles on a campsite can also keep them away from your tent (at least to a degree).

Any smoke from a campfire can also keep midges at bay – at least up to a point. Lighting a good bonfire can certainly keep midges away a little – but in order to avoid midges landing on and biting you, you may have to sit right in the path of the smoke.

Scientists are currently also working on creating a midge repellent using the plant bog myrtle, and it is believed that bog myrtle may be one of the most effective natural midge repellents. Bog myrtle’s citrus smell may mean that it works in a similar way to citronella.

Some say that taking garlic capsules can help reduce your attractiveness to midges, while others swear that taking vitamin B capsules (or eating lots or Marmite) do the trick. The efficacy of such folk remedies, however, is unproven, and their reported success rates seem to vary considerably – depending on who you talk to.

Avon Skin So Soft – Does It Work?

Another often discussed remedy to keep midges from biting is Avon Skin So Soft Dry Oil Body Spray. While not sold as an insect repellent, it does seem to work to prevent, or at least reduce, midge bites – at least for a while. Legend has it that when training in the Highlands, Marines and other members of the armed forces slather it on to avoid being bitten.

The oil may simply work initially due to the fact that is has a strong smell (and covers your skin) so that you are somewhat more difficult for midges to detect and find, and don’t taste as good when they do. Some say that it is the citronella in the product which does seem to be somewhat repellent to midges.

However, from personal experience (I am definitely someone attractive to midges!) the repellent effect seems to wear off very quickly, and it is, in any case, not entirely effective. Unless you are prepared to slather on amusingly large amounts, and reapply every ten to fifteen minutes or so to renew the effect, then this is only ever going to be a partial solution to the biting midge problem.

It is also worthwhile noting that while Avon Skin So Soft (and citronella essential oil) will prevent midges from landing on and biting you for a while, if you are in an area where it is particularly high in midges, they will still be all around you.

They can be infuriating – to say the least. A midge net in addition to the repellent you choose will stop them from flying into your eyes, up your nose, or into your mouth. If you have never been in bad midges, you really cannot imagine how bad it can be!

The best way to think about things, when visiting the areas of Scotland with a high midge density is that it is usually better to try to stay away from them, rather than trying to keep them away from you. Find breezes, head for higher ground, or simply find somewhere indoors until the problem lessens.

07. Biology

The Highland biting midge has a wingspan of just 1.4mm and weighs just an 8000th of a gram each. With the aid of a microscope, the biting midge Culicoides impunctatus can be distinguished from the non-biting Chironomidae by:

- The presence of female biting mouth-parts (it is only the female of the species that bites)

- Short fore legs

- Characteristic dark markings on the membranous wings which are folded, like scissors, when the insects are at rest or feeding

The wings of a midge beat faster than any other wings in the animal kingdom – 1000 times per second.

With an abdomen full of blood (from biting humans or animals), a single female midge can produce up to 200 eggs. In optimal conditions, with the right type of soil, around half a million midges can hatch from just one two square metre patch of ground. 25% of Scotland’s land area is perfect midge territory and there can be as many as 180,750 trillion midges in Scotland during the peak of the midge season.

Culicoides Impunctatus

The Scottish biting midge is of the genus Culicoides and its species name is Culicoides impunctatus. In Gaelic, they are known as ‘meanbh-chuileag’, which means ‘tiny fly’. Members of the genus are found on every continent except Antarctica, and at elevations of up to 4,250m on Mount Everest.

This particular species is prevalent in the Scottish Highlands but can also be found throughout the British Isles, across Scandinavia, other regions of Europe, in Russia and in Northern China. However, due to the challenges in positively identifying this species, is actual distribution is still unclear.

Culicoides impunctatus is just one of 37 different species of Culicoides midges that have been recorded in Scotland, and yet it is responsible for 70-95% of all the bites on human beings that occur throughout the country. Of course, as well as biting humans, they also play a crucial and pivotal role in Scotland’s ecosystems. There is also a wide range of non-biting midges throughout the country, which also play their roles without posing a problem for human beings.

08. The History of the Scottish Biting Midge

Culicoides have been on this planet for a very, very long time. Specimens of this genus related to species alive today have been found preserved in 120 million-year-old amber in Lebanon, and in Scotland, in amber that dates back 75 million years.

Midges have played a role in the history of Scotland throughout its long and fascinating past – as much – if not more – a part of the country as unicorns, thistles, tartan and haggis.

Bonnie Prince Charlie’s encounters with midges while hiding in the hills after the Battle of Culloden have been vividly described, and there are also gruesome tales from Scotland past of people being left tied to a stake in a midge field as a form of torture.

The presence of biting midges in Scotland has shaped land use over the centuries, with implications for agriculture, forestry, outdoors recreation and, of course, tourism.

Scotland’s midge fauna was first scientifically described and investigated in the early 20th Century but it was not until the middle of the century that Scotland’s midges were investigated in more depth. The University of Edinburgh set up their ‘Midge Control Unit’ in 1952.

Interestingly, though strides were made during this period in our understanding of these creatures, there was a lapse in research of some thirty years or so before modern approaches to the ‘midge problem’ took over. These have produced a wealth of information on population dynamics and the life cycle of the midge which have helped to determine potential ‘solutions’ for humans to live in harmony with the biting midge.

What you should do next...

- Browse our plots to claim your title of Lord or Lady of the Glen

- Discover the masjetic Kilnaish Estate

- View our fun gifts and accessories, inspired by the Scottish Highlands